Like so many things in life, ignorance is paradoxical.

Is it possible that

ignorance is an intelligent response to the universe, and conversely, the lack

of ignorance is a stupid and self-destructive response?

As usual with this blog, we start with politics.

No politician who admits ignorance of anything could ever be

elected even to any political office, even the office of Chief Dog Catcher. Therefore, accepting this reality, all

politicians know that they need to know everything or at least, pretend to know

everything. A politician must have all

the answers and no unanswered questions.

The most successful politicians will always have a clever and ready

answer to every question asked of them in any forum, a public meeting, a TV interview, whatever.

Have you ever heard a politician dare to answer a question

of any kind by saying, “I really am ignorant of that. I am happy to admit that

I cannot answer that question, and I probably never will be able to answer it.”?

That kind of political animal, if it ever existed, has been extinct

for a long time.

No politician could

ever admit, especially to himself, how little he knows know about anything. The

modern political animal may actually know very little about almost everything,

but he or she must have an opinion about everything. That opinion must be

strongly held and can never change, even in the face of completely

contradictory facts. In order for this

to work, the politicians themselves must strongly believe in their own

omniscience.

The need to believe strongly in one’s own omniscience

creates problems. For one thing, it

means that political beliefs must be totally disconnected from science and

changes in scientific knowledge.

Even more troubling, it means that politicians must be, in part,

have narcissistic personalities. If the politician has only a small dose of

narcissism his personality, he may be

content with being elected dog catcher, but if a politician is a huge

narcissist, he or she is per se eligible to run for the top office of President.

Think Gary Hart, John Edwards, George W. Bush, Sarah Palin, Bill Clinton. In fact, think of any major politician and

try to imagine that person discussing how comfortable he is with his own

ignorance of everything. That kind of

person does not exist.

The public is an integral part of this sham as the

politician. The public inflates the politician’s narcissism with political ads,

signs, cheers, big rallies, and political events of all kinds, not to mention

donating money, buying the candidates books, political buttons, etc. All of this feeds the monster of political

narcissism.

This is one reason why we have such a love-hate relationship

with our political leaders and why we are always so disappointed in them. We

expect them to be omniscient. When it turns out that they are clearly not

omniscient, but continue to think that they are, and then make mistakes as they

blunder along, we become disappointed. Case in point: Barak Obama. Another case, George W. Bush.

|

| King Tut |

In some nations, the political leader is thought to be so

omniscient that he is actually deified. Of course, the political leader plays

along with this and encourages it to the max. But does any man really believe

that he is really a god? The answer is

that many actually do. Think of Fidel Castrol, Hugo Chavez, Papa Doc Duvalier,

Stalin, Hitler, and all the monarchs and sultans throughout history.

Science is on the other side of the paradox of ignorance.

Science values ignorance. Scientists value questions more than answers. Answers

are boring and uninteresting unless they lead to more questions. Scientists think

that there can be no discovery and no new knowledge without ignorance of that

which is sought to be known. The greatest scientists are those who have the

most questions. One of the ultimate

questions in science is how much of the unknown is unknowable?

How different from the political sphere is that?

Neuroscientist,

Stuart Firestein, has written a book entitled “Ignorance: How it Drives

Science.” Recently, on NPR’s “Science Friday” show, Firestein explained to

interviewer Ira Flatow how science is

really pursued among scientists:.

When

we go to meeting together and talk or go out to the bar and have a beer or

whatever, we never talk about what we know. We talk about what we don't know,

what we need to know, what we'd like to know, what we think we could know, what

we may not even know we don't know just yet and things of that nature. And

that's what propels the whole operation along.

Firestein argues that we put too much emphasis on answers

and not enough on questions. He says

that if we start with a hypothesis, it is likely to lead us to the wrong

answer. Scientists need to start, he says, only with collecting facts and let

the theory come later.

Firestein is fascinated not by the known unknown but by the

unknown unknowns. He is interested more in the limits of ignorance than the limits

of knowledge.

One of the

best quotes in the interview is from the comic Emo Philips, who says “I

always thought the brain was the most wonderful organ in my body, and then one

day I thought, wait a minute, who's telling me that?”

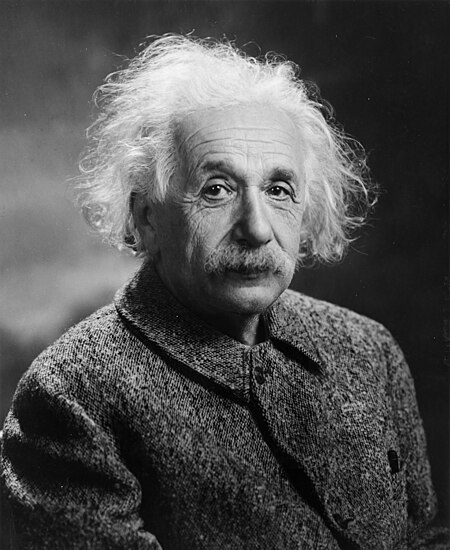

Einstein had a visual metaphor

about knowledge and ignorance. He saw us as inside a balloon containing all of

our knowledge. As we gain more

knowledge, the balloon grows, and the surface of the balloon grows, which means

it touches on more and more of that universe of what we don't know. So that the

more we learn, the more we don’t know.[1]

Firestein and Einstein are not alone in their

comfort with ignorance. The eccentric

Nobel Prize winning Richard Feynman who works on quantum

electrodynamics (the field of science concerning how light and matter interact)

said in his book, “The Pleasure of Finding Things

Out” that “I

don't feel frightened by not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious

universe without having any purpose - which is the way it really is so far as I

can tell - it does not frighten me.”

Firestein and Einstein are not alone in their

comfort with ignorance. The eccentric

Nobel Prize winning Richard Feynman who works on quantum

electrodynamics (the field of science concerning how light and matter interact)

said in his book, “The Pleasure of Finding Things

Out” that “I

don't feel frightened by not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious

universe without having any purpose - which is the way it really is so far as I

can tell - it does not frighten me.” |

| Los Alamos Id Photo of Feynman |

When awarded the Nobel Prize Feynman

said that he was uncomfortable with accepting it because when a person held a prize

or gained a position of authority, people are inclined to think that he must be

correct, and Feynman was uncomfortable with that.[2]

Don’t even try to imagine a politician trying to think this

way.

No comments:

Post a Comment